Epoché.

Disinformation education in real time

Disinformation is rampant in our society. Organizations fighting it are having mixed results. What is the solution?

This concept explores an education-based approach to solving the problem of false news through education, critical thinking skills, and media literacy.

Role

Beginning as a school project, I assumed the role of lead designer, UX researcher and creative strategist.

Duration

~6 months (January 2021-June 2021)

Overview

The United States Government and Big Tech organizations are having a difficult time identifying, tracking, and preventing disinformation. As a project that started in a class at Columbia University, we took the idea of, “promoting resiliency against disinformation campaigns” and built it into a proposed service.

Epoché establishes the framework behind the notion of using education in order to promote information and news literacy as the methodology behind this solution.

Team

Engineer: Eric Webb

Tools

Figma, HTML/CSS, JavaScript, Webflow, Python, Pen & Paper

Scope

UI/UX Design, Prototyping, Wireframing, User Research, User Testing, Information Architecture, Design Systems, Software Engineering

Location

Louisville, KY (Remote)

Foundations

At many schools across the nation, a partnership exists between academia and the United States Government forged through a course called Hacking 4 Defense. In this course, complex problems being faced by government agencies are presented to students in hopes of inspiring innovation and working toward solutions that will benefit our nation.

While taking this course at Columbia University, Epoché began under the original moniker of ‘PropaGOTCHA’.

Problem Statement:

When my class began Hacking 4 Defense, we interviewed with our professor and then were assigned one of six different problems.

What you see here is the problem description that my team and I were assigned.

In summation, United States Cyber Command (USCYBERCOM) needs a real-time way to flag open-source content associated with disinformation to minimize it’s spread while also enabling citizens to be more resilient to disinformation campaigns.

This project is the story behind solving this problem.

Challenge

We were directed by USCYBERCOM, in coordination with interagency partners like the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), to seek a way to lessen the potency of disinformation campaigns. This included providing viewers with an awareness that they might be looking at content associated with disinformation.

CYBERCOM noted that they had contracted with open-source companies to identify disinformation campaigns in the past, but these efforts did not help notify consumers in real-time that content they were viewing might be associated with disinformation.

By providing such a real-time notification, CYBERCOM desired to empower the average internet user to identify and resist the effects of potential content containing disinformation.

Defining Goals

With our challenge issued and a long road in front of us, I began by interviewing 6 randomly selected individuals, aged 22 to 53, about how news, social media, and how disinformation was affecting use of these platforms.

This initial interview served as a very broad introduction for how the general public views the current situation. Providing this scope would help us hone in on our problem statement and visualize a solution that might be most effective in addressing it.

I organized their most relevant responses and categorized them by the overarching problem that they pointed towards:

Affinity Diagram

The categories in this diagram immediately hinted at the three main issues that we would be faced with. We would have to circumvent the traditional methods of fact-checking, identify where news outlets were failing with the delivery of their stories, and find a way to avoid the approaches taken by notable tech giants.

Market Assessment

Initial interviews hinted at it, and news reports can’t help but throw it in our faces; disinformation is a notable issue in society. So far, a number of organizations have applied their own ways of stopping or suppressing it.

Before we even began to innovate, I used our initial interviews as a guiding light to do an in-depth competitor analysis. Various companies have tried their own methods at slowing the spread of disinformation, and I deemed it important to take a closer look and assess their relative strengths and weaknesses, as well as what is working and what isn’t.

Aside from fact-checking services done by Big-Tech corporations like Facebook and Twitter, I also considered smaller companies and browser extensions to gain a comprehensive understanding of the issue at large. This look at the market landscape explained how these specific companies attempted to address disinformation and how it impacted the user.

Big Tech

vs.

Browser Extensions

Surveying the User

After identifying our competition, I sought to more deeply understand how our users saw the current solutions succeeding, failing, and their feelings overall towards the platforms. To better understand how users felt about these tools available against misinformation, I surveyed over 60 people of different ages, professions, and political spectrums.

The specific information displayed in the user interface, as well as how it is displayed, will determine whether a user will commit to the application or not.

Users value a variety of different factors when determining whether to share an article online or not.

Users consider different pieces of information more important than others when making the decision to share or not.

However, with quantitative data, there are opportunities to misinterpret the results if not paired with a contextual inquiry. Specifically, I wanted to know how users felt emotionally about the experiences provided by these apps and how they interpreted the information that they were being given by them.

To accomplish this, I asked 9 additional interviewees to use these tools in front of me and to describe their experience, this time with individuals who identified as active in current events and who received them from a diverse assortment of media.

The interview was structured with open-ended questions to make sure that I did not direct them toward any answers and so that they included all aspects of their sharing and research habits, as well as potential pain points.

The goals behind this set of interviews were to be more precise than the first. Specifically, I wanted to:

Understand how users decide whether or not to share an article

Discover information or online tools that users felt increased their confidence in interpreting news

Figure out the thought process behind users reading articles online

Secondary Research Check: Comparing User Research to National Surveys

Data provided by the PEW Research Center and Statista.com

50%

Adults that deliberately or unintentionally shared disinformation online in March of 2019.

67%

U.S. adults that say misinformation causes a great deal of confusion around the basic facts surrounding current issues.

52%

Those that think that they are regularly surrounded by potential disinformation in the news.

66%

Americans who are not confident that tech companies will prevent misuse of their platforms to affect an election.

Research Discoveries

Putting the data from the interviews and surveys together showed an interesting diversity between what users considered important when determining the reliability of a platform. When considering disinformation, every single user is important, as it’s impossible to know who ‘patient zero’ will be. In keeping with this, we didn’t want to include types of information only because they had a larger majority of users in favor of it.

Thinking back on the data from Statista.com, 52% of Americans today think that they are exposed to disinformation in the stories that they read every day, as well as another 34% of Americans that are open minded to the notion that malicious content is out there.

I entertained a curious question; if a user were given tools to discover disinformation on their own, would they be more likely to learn how to spot it and become more resilient in the future?

After taking a step back and looking at the problem from a more broad perspective, an interesting but critical discovery surfaced for me about how entities are trying to stop the spread of misinformation; current solutions are all reactive, while none were attempting to be proactive.

Embracing this, I was able to further define our problem:

How might we educate users with the knowledge to not only prevent misinformation, but to seek it out and weaken the potency of false news stories overall?

This led us to establish some conclusions for the project;

We had to create a solution that established and inspired trust with the user

We could not make a definitive decision on the truth or factualness of news articles for them

Rather than fact-checking, we would focus more on the promotion of critical thinking and information literacy

We had to develop a platform that could incentivize participation from as wide a population as possible

Personas and Archetypes

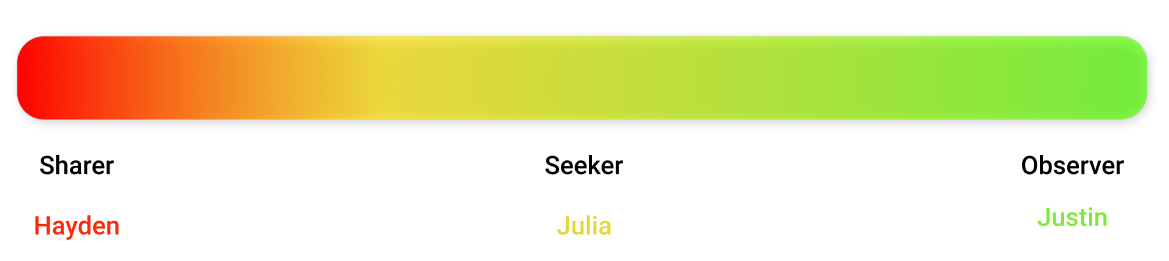

Understanding the above points, we opted to create a service that caters to three broadly defined user archetypes, each with their own personal needs, desires, and interests when it came to our product’s interface, and more importantly, whether they would determine it effective or not.

Sharer — Hayden

Places emphasis on debunking sources outside of his own preferences

Decision to share is based on the provocativeness of headlines and their topics

Seeker — Julia

Does a decent amount of research, but all conclusions are based off of her own decisions

Wants to more closely analyze articles, be more sure of her decisions, and easily compare findings to other sources

Observer — Justin

Wants to be confident when searching for current events

Eager to be able to explain why he considers some material factual and others not

Identifying these three unique archetypes allowed us to clearly establish a preliminary set of goals that catered to each type of user. This enabled us to expand upon the types of features that would not only be appealing to them individually, but also critical in addressing our overall problem statement. These personas were integral to the formation of our design decisions and we often referenced them when creating features.

Initial Wireframes and Feedback

At this point we were deep into a virtual semester and spent a bit of time on research. We wanted to expedite progress and feedback to build a working design that would meet project due dates, so we opted to quickly move from baseline paper lo-fi wireframes into some digital mid-fi mockups. We decided that a Chrome extension would let the product act as we wanted to and moved forward with pursuing that solution.

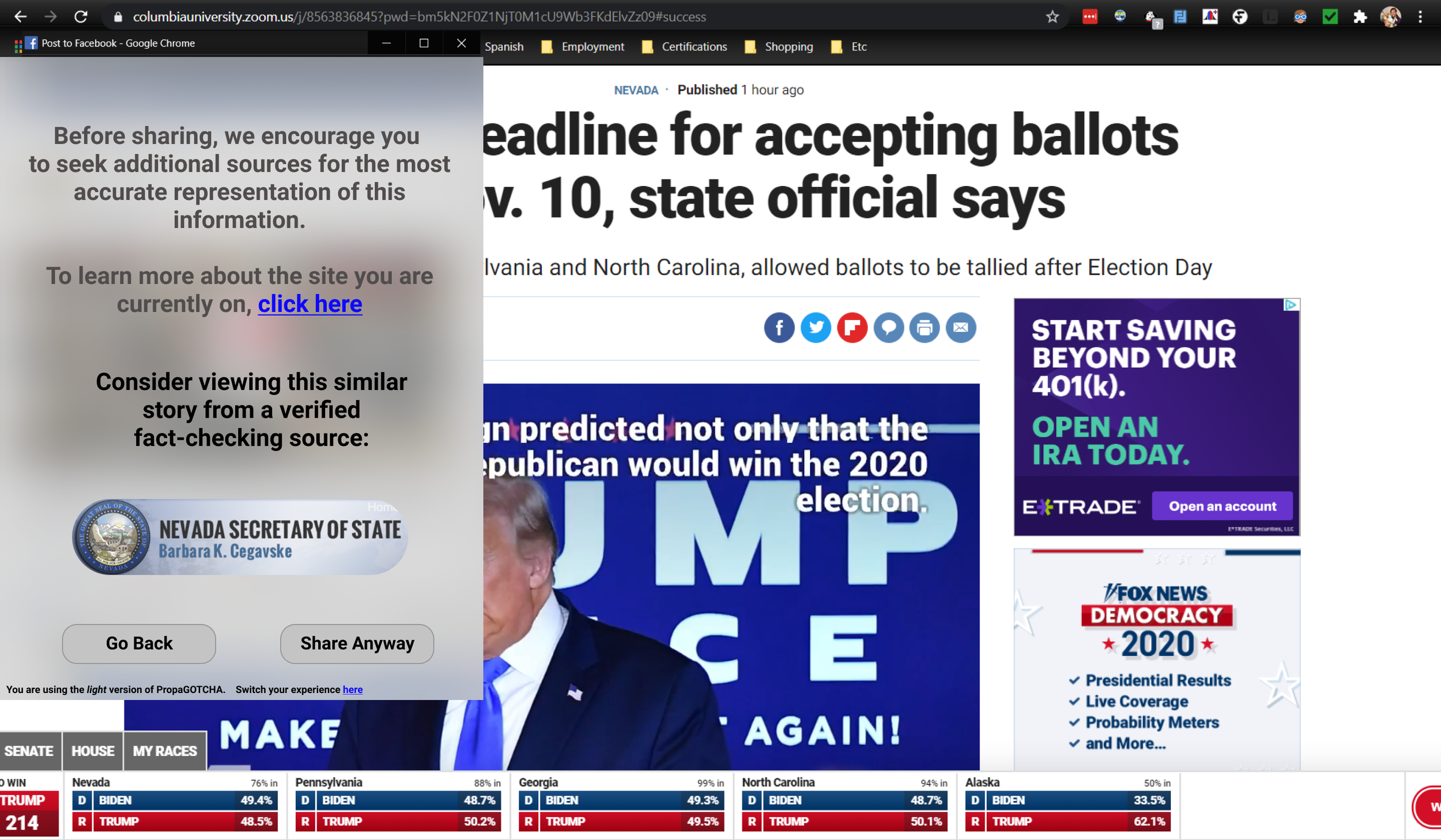

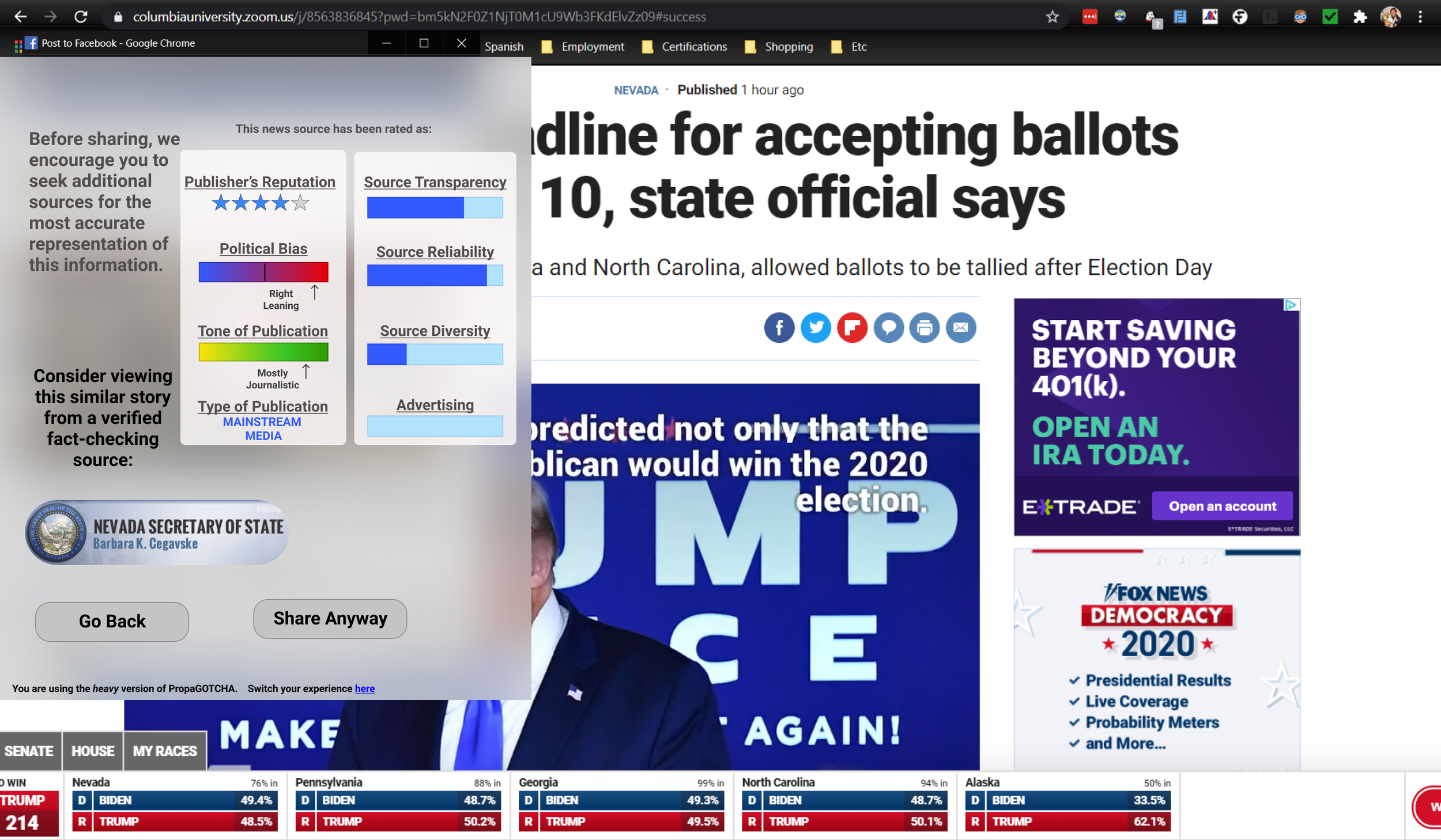

Our establishment of our user archetypes gave us another possible lead; what if each type of user required a different level of information or ‘intervention’ to stop them from sharing?

To expand on this, we initially developed three different designs:

A light UI that removes all unnecessary tools for Sharers that aren’t likely to use them

A medium UI that provides the top-rated tools for Seekers

A heavy UI with all available tools for Observers who research, but don’t share

Conceptually, our stakeholders, including our sponsor at USCYBERCOM, a fellow at the RAND Organization, and tenured professors at Columbia, approved of the research and expressed interest in its application.

Yet, with praise also came critiques. For both our stakeholders and user testing, these critiques boiled down to:

Ambiguity in our instruction process

Confusion on sources of our data/why we identified elements as misinformation

An unclear UI that didn’t differentiate our process from competitors

Lack of originality and an inability to capitalize on our idea of being proactive

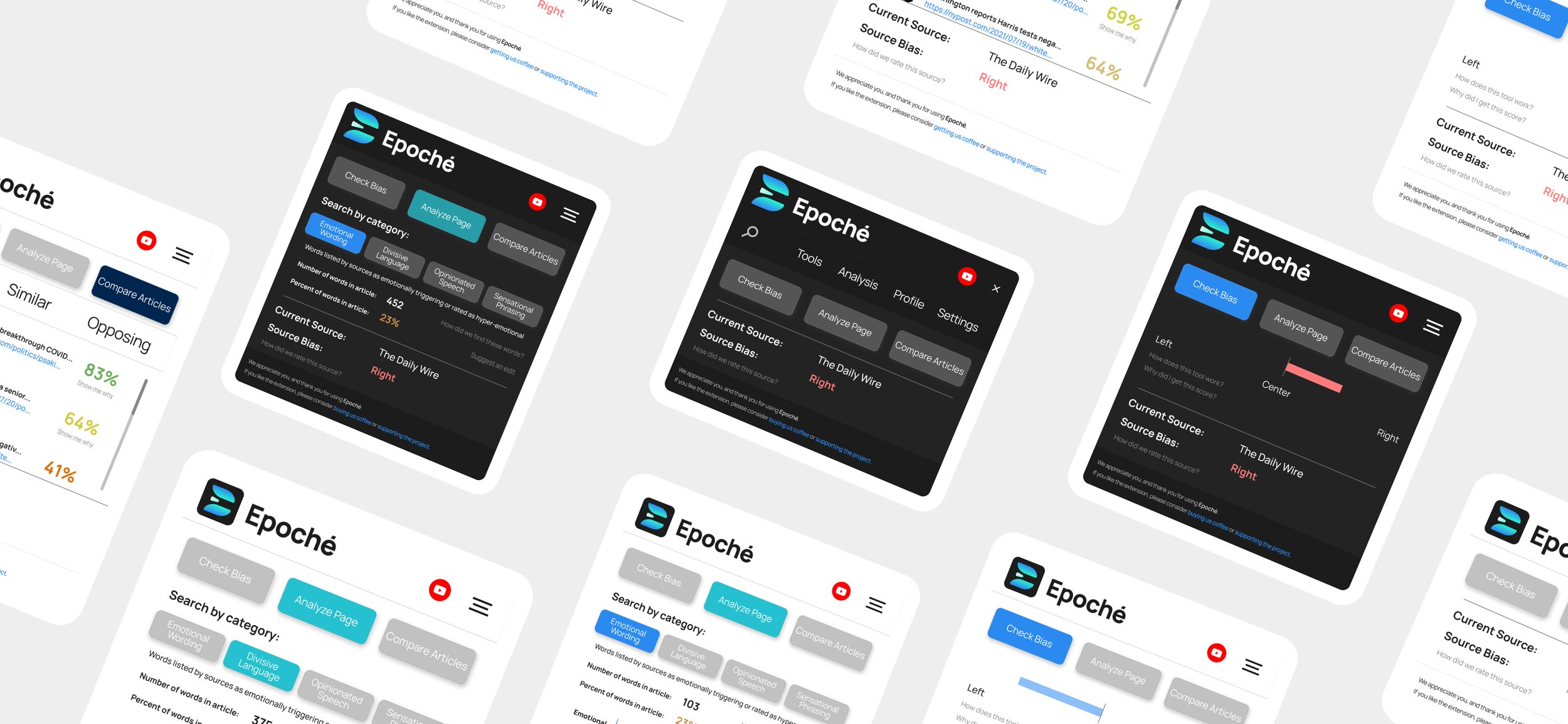

Refining the Concept - Hi-Fi Prototypes

The research was right, we simply weren’t innovating enough to be a product that was different from our competitors.

Eric and I looked at the research again and put a bit of thought behind what it would take to make an impact. We realized that we had the answer all along, we just weren’t using it.

Users had already shown that giving them forced information just didn’t work. One would have to want to actively interact with the extension, to want to use the tools, to be curious and interested.

This was the thought process we needed and led us right to our solution.

Building Unique Tools

Internal Bias Detection

Using an algorithm that monitors what news sites the user visits, we assigned ratings to all major news sources on a scale from 0 to 5, 0 being far left, 5 being far right.

Based on this scale, we would recommend articles from the next closest number on the scale with the hope of bringing users closer toward more neutral sources within their political spectrum.

Lexical Page Analysis

We compiled multiple excel spreadsheets, each containing lists of words that are associated with different categories, such as ‘emotional, ‘divisive’, ‘opinionated’, and so on.

Using this tool, Epoché acts as a glorified CTRL+F and highlights all words on a page while also reporting what percentage of the article is ‘charged’ and what category is the most prevalent.

Article Comparisons

Using an algorithm that uniquely compares search data from all relevant news sources via their search bar, we are able to present to the user articles of the same topic and their respective lexical analysis rating.

The user can filter by their own political bias, or even view opposing articles if they so choose.

These tools tested much higher with our user group in another round of interviews and resonated with our stakeholders.

Comments included:

“This is exactly like something that I have been proposing as a deterrent to disinformation.”

-Chris Paul, Policy Expert at RAND

“I see tremendous potential for our analysts and to the general public in an application like this.”

-Mike Meglino, Senior Advisor at USCYBERCOM

“This feels unlike any ‘fact-checker’ out there right now, I actually feel more informed and in control when I go through news now.”

-Response from Contextual Interview

Having addressed major pain points such as:

Lessening the potency of disinformation

Providing a real-time way to flag content that may be disinformation

Enabling resiliency against disinformation

We also managed to get the attention of leadership in the National Security and Innovation Network, which leads us into our next segment.

Innovation Meets Ambition

Selected as one of the top candidates in the Hacking 4 Defense class after it’s revisions, Epoché was selected as a candidate in the NSIN Vector Program. This initiative, which takes top H4D projects from across the country and develops them into potential businesses, pushed our project to reach further and develop our extension into a larger service.

Pivoting from our finalized extension design done in our former class, we were challenged to make a web service that could provide educational content and instructional quizzes to help reinforce our mission of promoting information literacy. Vector provided resources that helped us build pitch decks, practice presentations, incorporate as a business, and strategically plan how to seek out, appeal to, and gain defense contractors.

That challenge lives on to this day as Eric and I continue to design, code, and plan on implementing Epoché in a way that will be best for it’s success.

As new designs and relevant actions evolve with this project, I will include them here and further expand the information in this case study.

Updated: December 15, 2021

After Action Review (AAR)

Build a Foundation of Research

During this project, I found myself constantly moving back and forth between research and prototyping. New discoveries were constantly changing the design format of our solution, which ended up proving to contribute the most to the time cost of the project as a whole. The research we conducted was effective, however, I can think of a number of scenarios where it could have been organized to be more efficient.

Staying Focused

While this case study is more streamlined, with the introduction of the NSIN Vector program, a lot of the focus in the project pivoted from design solutions to business case scenarios in order to be competitive with the other teams in the entrepreneurial program. Splitting the tasks between our team, along with programming a working front and back end solution proved to be time-intensive and distracting in the end.

If I were to do it all over again, I would have narrowed the scope of my vision and committed solely to building designs and double down on research; the elements upon which all the other things could have easily stemmed from as we progressed with the project.

Team Communication

Many of the tasks completed with this project were issued during weekly progress reports. Looking back, I would have found significant value in conducting joint-production sessions where the team could get together and solve our problems in real-time rather than in weekly increments.

Get Excited

It was incredible to work with such professionals and to build something that had real value with a good friend of mine. I loved the opportunity to participate in a product cycle of my own design, as well as working to create something within the sphere of misinformation that put the user’s voice first. The project is the closest to my heart, as it was a passion project from beginning up until now as I continue to work on ensuring it is a success.

The Future of Epoché

The Alpha release for Epoché is currently under review by the Chrome Extension store and will launch upon approval.

Find out more about our progress at www.epoche.app